I personally think that one of the best things about a sunny summer day is gathering with friends and family to enjoy an old fashioned flamed barbecue. My husband would argue that it’s a lot of work to cook (he just does the actual “flaming” part, none of the preparation of course…but I’m told that’s where the skill is…) but we all agree that it’s well worth the effort for the delicious aroma and flame-grilled flavour! We could achieve the same look with an oven (domestic, not lab ovens!) but it wouldn’t have the flavour we adore.

The art of preparing your meats and vegetables and the technique of grilling has become a little bit of science of its own. There’s a “World Series of Barbecue” and “The World Championship Barbecue Contest” among other prestigious events where talented barbecue technicians show off their skills! I think this tends to be in the USA rather than here in the UK where I believe we are having our soggiest summer in many years.

We looked once before at the phenomenon called the Maillard reaction, scaring ourselves slightly with the realisation that some of the char-grilled and tasty burnt bits on our burgers can be carcinogenic, but wanted to see what else the field of chemistry can offer in terms of benefits of this fine form of food.

Enthusiasts would probably tell you that the secret spices they use, or special types of chipped wood in their charcoal influence the flavour of the food but, according to chemistry, it really does come down to the heat above all else! Like in the laboratory, if your heating method isn’t efficient or properly regulated, it just won’t work. That’s one reason why we love our Hotplate Stirrer Kits (which are currently on special offer by the way!) – they’ve got three separate safety circuits regulating the temperature control so you can be extra confident when you set the limit! The browning of the surface of the meat is the Maillard reaction mentioned above taking place; a chemical reaction between amino acids and reducing sugars.

It isn’t only meats which are affected by the Maillard reaction; This is also responsible for toast, biscuits, fries, the colour of beer, roasted coffee, the crust of cakes, and maple syrup! Apparently scientists in Venezuela have developed a novel method of keeping beer fresh by adding the drug aminoquanidine and a chemical called 1,2-diaminobenzene (1,2-DAB) to the beer thus manipulating the Maillard reaction but they aren’t sure how exactly. I can’t be sure if this is true or only a rumour though!

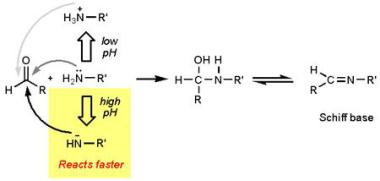

So what can the chemist bring to the barbecue party to earn their place at the table? Let’s look at marinades. These have a key role in adding flavour to our barbecue and are basically a mixture of acids, oils, and herbs/spices. Acid has a big role as, like heat, it also denatures proteins and creates “channels” for artificial flavour and moisture to seep in, thus giving a juicier taste. You can’t use this acidic environment for too long though as it actually results in advanced degradation of proteins so the outer layers will become mushier, and actually brown less on the grill as acids brown less readily. The Maillard reaction reacts more readily at high pH values.

http://blog.khymos.org/2008/09/26/speeding-up-the-maillard-reaction/

You need to find a balancing point to get the most flavour from the heat and the acid. As cell membranes are mainly composed of a phospholipid bilayer, oils can easily cross this barrier and further penetrate into the meat, carrying additional flavours with it. What mixture or proportions do you find works best for you? Tools like the DrySyn Vortex Blend would be fantastic for mixing marinades in beakers but I don’t think I’d be allowed to take one home!

According to the American Cancer Institute, an added bonus of marinating meat is the protective effect against harmful carcinogens – cancer causes compounds – that are produced from the barbecue process.

At high temperatures, amino acids + sugar + creatine (substance found in muscle), react to produce cancer-causing compounds collectively called heterocyclic amines, according to the cancer institute. Another class of carcinogens, Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), are formed when fat drips onto hot coals or stones. During flare-ups or via smoke, these toxic chemicals travel and adhere to the surface of the meat.

One way to stop these harmful compounds in their tracks is by marinating. Nutrition adviser with the cancer institute, Karen Collins, says that marinating meat can reduce the amount of heterocyclic amines produced by as much as 99 percent .

“A marinade may act as a “barrier,” keeping flames from directly touching the meat. Or the protective powers may be due to typical marinade ingredients, such as vinegar,

citrus juice, herbs, spices and olive oil. So think of it as sunscreen for your meat.” Cancer-causing compounds can be further avoided by cutting off any charred meat before serving”.

So with the right ingredients, a “dash” of chemistry, maybe a cold drink, – we can turn up the heat and feel smug that we’re all chemists when we barbecue!